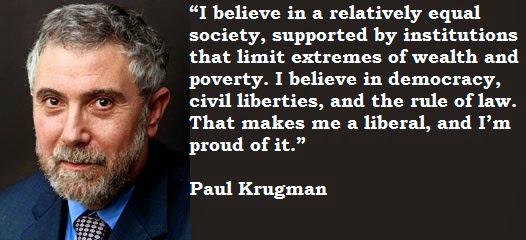

In “retaliation” to Paul Krugman’s gloomy outlook on Canada’s housing prospect, actually, impending “Bubble Implosion” …

Paul Krugman: “Think there is no housing bubble in Canada ? Think again.”

TD Bank to Paul Krugman: You’re wrong about ‘vulnerable’ Canada

MICHAEL BABAD The Globe and Mail

TD takes on Krugman

Toronto-Dominion Bank is taking Paul Krugman to task for suggesting Canada may be headed for trouble.

It would take a shock for that to happen, TD economist Diana Petramala says.

In his New York Times blog a week ago, Mr. Krugman noted that he’d been to Canada to get an honorary degree from the University of Toronto, which got him thinking about the Great White North, and how it could be a test case in the post-recession era.

The Nobel prize winner said many observers believed the financial crisis was a banking one, and felt the economy would rebound at a fast pace when the financial services sector was stable.

While the industry indeed calmed down, he said, the economy did not pick up, leading some economists, including Mr. Krugman, to think that other problems were at hand, notably depressed housing and consumer debt.

“Famously, Canada’s old-fashioned, boring banking system avoided getting caught up in the global financial crisis,” the economist wrote.

“And for a while Canadian housing prices lagged those south of the border.”

Of course, Canadian property values shot up, as did the key measure of consumer debt to disposable income.

“So if the new, non-bank-centred view is right, Canada ought to be quite vulnerable to a big deleveraging shock despite its boring banks,” Mr. Krugman said.

“Of course, people have been saying this for several years, and it hasn’t happened yet – but remember, the U.S. housing bubble took a long time to pop, too.”

Mr. Krugman is not alone. Others from outside the country have also warned they believe Canada is headed for trouble.

Canadians, of course, are all too familiar with warnings from the Bank of Canada to get their household finances under control, and Finance Minister Jim Flaherty’s four attempts to cool down the real estate market.

The latest numbers from Statistics Canada show the household debt burden continuing to ease from record levels, while home sales have fallen sharply though prices have held up.

That’s the background.

TD economist Diana Petramala agrees that there are risks associated with the housing market and consumer debt, but that there are “important counter-arguments” to Mr. Krugman’s worth noting.

In a research note, she pointed out the warning signs in the run-up to the U.S. crisis, which included rising mortgage interest costs and mortgage delinquencies that climbed along with consumer debt.

“The charts show that Canadian households are far less financially vulnerable than their U.S. counterparts were heading into the crisis,” Ms. Petramala said.

“Largely owing to a continued low interest rate environment, mortgage interest costs as a per cent of personal disposable income have fallen despite the sharp rise in the debt-to-income ratio,” she added in her report.

“Meanwhile, while mortgage delinquency rates in Canada and the U.S. were similar during the 1990s, the per cent of mortgages in arrears 90 days or more in Canada is about a third of what they were in the U.S. leading up to the 2008-2009 crisis.”

Ms. Petramala cited the “riskier lending practices” in the U.S. between 2002 and 2007, and the tighter restrictions now in place in Canada.

Add to that the fact that incomes have climbed at a faster pace in Canada since the recovery began, helping to ease “some of the recent overvaluation” in the property market.

That’s not what happened in the U.S.

“We would be concerned should we see a further increase in household indebtedness or an acceleration in home price growth – both of which are certainly a risk given a continued low interest rate environment,” Ms. Petramala said.

“However, absent of a negative economic shock, excesses are expected to continue to unwind in an orderly fashion.”

Paul Krugman warns Canada vulnerable to a ‘big deleveraging shock’

By Jennifer Kwan | Balance Sheet

When certain names sound off about the Canadian economy, we should pay attention. This time it’s renowned economist Paul Krugman, who over the weekend stated Canada “ought to be quite vulnerable to a big deleveraging shock despite its boring banks.”

The Nobel prize winner suggested Canada is an important test case for what lies behind the 2008-09 recession and the sluggish recovery. In other words, if the U.S. experience is anything to go by, Canada might be undergoing a housing and debt bubble, and if so, he advised people to watch what happens next.

With interest rates at ultra-low levels and Canadian household debt and housing market stabilizing, market strategists and economists like Krugman here are scrutinizing every bit of economic data for clues on what the economic outlook will bring. That’s why comments by big name economists outside of the country add an important dimension to the debate.

Krugman, in Canada on the weekend to receive an honorary degree from the University of Toronto, wrote in the New York Times that many economists once believed that stablilizing banks would solve the fallout from the global financial crisis.

Take for example the U.S. economy. Banks were stabilized, but the economy remained depressed and is still digging itself out the big deep hole called the Great Recession. That forced many economists, including Krugman, to a take view of the world that focused on non-banking issues, especially the broader effects of collapsed housing and the overhang of private debt.

That’s where Canada now fits in as test case. Krugman sees potential red flags in the large spread between U.S. and Canadian house prices, and the fact that Canadian household debt levels are climbing even as U.S. ones are declining.

“So if the new non-centered bank view is right, Canada ought to be quite vulnerable to a big deleveraging shock despite its boring banks,” he wrote. “Of course, people have been saying this for several years, and it hasn’t happened yet — but remember, the U.S. housing bubble took a long time to pop, too.”

“I’m not exactly making a prediction here; but I guess I believe in the debt overhang story enough to be worried, and Canada is certainly an important test case.”

Bank of Canada warns on housing, debt

Economists and policymakers have for months consistently voiced concern about soaring Canadian household debt levels and the housing market, with the federal government most recently targeting consumers’ ability to borrow by tightening mortgage lending rules in a series of measures.

Last week, the Bank of Canada reminded Canadians that those risks to the economy remained elevated, even though they appear to have stabilized somewhat in recent months.

The central bank went on to highlight an overbuilt and overpriced condo market as a key concern for households in its latest review of the health of the country’s financial system.

“Any correction in condominium prices could spread to other segments of the housing market as buyers and sellers adjust their expectations. Such a correction would reduce household net worth, confidence and consumption spending, with negative spillovers to income and employment,” the bank said.

It’s a domino effect. These adverse effects would then weaken the credit quality of banks’ loan portfolios and potentially lead to tighter lending conditions for households and businesses. “This chain of events could then feed back into the housing market, causing the drop in house prices to overshoot,” it noted.

Too early to judge?

While still a bit early, many Canadian economists see some variation of a soft landing including Doug Porter, chief economist at BMO Capital Markets.

Canada should not find itself in the same situation. House resale data on Monday that showed existing home sales rose for a third month in May added more ammunition to that view, leading Porter to proclaim, “Sorry to inform you, but ‘The Great Real Estate Crash of 2011…no…2012…no…2013’ has been postponed until 2014, or until further notice. More seriously, we believe housing remains on track for a fabled soft landing.”

Back to why the Canadian experience will likely end up being different than the U.S. The main difference between the two countries is simply that lending standards were generally maintained in Canada, and the sub-prime sector never took on a sizeable share of the market. Thus, the view is folks that got loans in Canada generally have a very reasonable likelihood of repaying them. That was not the case south of the border in the years leading up to the crisis, says Porter.

“If he (Krugman) is worried about the housing market and the build-up of household debt, then he should join the line,” he adds. “I think the situation does warrant caution and monitoring, but we continue to maintain that housing will not follow the lead of the U.S.”