If you haven’t been to Toronto in a while, you might not recognize the place. The skyline is starting to look a lot like Manhattan. And it’s not just the new buildings that resemble New York. So do the housing prices.

Real Estate agent Kevin McCarthy showed me around “Museum House,” one of Toronto’s many new luxury towers. A 2000-square foot, two-bedroom and den suite is listed at $2.1 million CAD.“The finishes are of the highest quality.

Features such as every suite has direct elevator access, and you step out your front door, and there are world class dining, and shopping, and theater, there’s everything here,” said McCarthy, showing me around.

(Illustration: Manya Gupta)

Amy and Chris Poole are looking for something a bit more modest. They’ve been on the home hunt since October and are currently living in a small rental with their two-year-old daughter. Most of their possessions are in storage.

“I mean, this is not our furniture; this is a furnished executive rental,” said Amy. “We want our stuff, we want to unpack our belongings. We want our home, we want to plant our feet.”

Amy and Chris have lost out on four offers and backed out of three others. They say competition at open houses is so intense that they’ve seen things get physical. Chris described a recent open house they attended.

“The listing agent is backed into the corner by the fireplace, and somebody is standing there being quite loud saying, ‘I’m going to work with you, I’m to make sure we get this property, whatever it takes, 120, 130 percent over asking, I’ll do it,’ just to try and intimidate everyone else.”

Amy added, “That was actually the last open house we went to because you just walk through and everyone is sizing each other up, giving each other bad looks.”

Toronto prices are being driven by a perfect mix – record-low interest rates, lack of inventory, and a stable Canadian economy.

Chris says he’s just not willing to pay above a certain amount for a three-bedroom place. He and Amy got uncomfortable when I asked how high they’re willing to go. But Chris said, “It’s over a million, but it’s not too much over.”

That’s a lot of money. And Chris is worried that he’s potentially investing in a bubble, a bubble that could go pop.

Home prices in Toronto have appreciated about 85 percent over the past decade. The market took a short, moderate dip in 2008, but has marched steadily northward since then.

Ask economists and housing experts where they see home prices heading in the next few years… there’s no consensus.

“My forecast is, this year, probably price growth of 2 or 3 percent. 2013, probably a price decline of about 4 percent decline,” said Craig Alexander, chief economist with TD Bank.

“We’ve penciled in around 25 percent price decline,” said David Madani with Capital Economics. (Madani emphasizes, that’s a rough estimate over several years.)

“We just don’t know,” said Phil Soper, president and CEO of Royal LePage Services, a real estate company.

The big fear in Toronto, and even more so in high-flying Vancouver, is this: Is Canadian real estate at risk of an American-style collapse?

Phil Soper says no. He says Toronto today is not like the US a few years ago.

“The rate of price appreciation is much less than you see in the United States, or in countries, such as Ireland that had real busts. The Irish situation, for example, from trough to peak, (was) four times as great a price appreciation as we see in Canada today.”

Soper says the rise in home prices in big Canadian cities like Toronto has been slow and steady – Toronto is the tortoise that’s moved ahead of the hare. And now, real estate in greater Toronto is suddenly more expensive than metro San Francisco or the New York area. (It’s hard to say that with absolute certainty though, as Toronto calculates home prices by average, whereas American real estate figures use median. Remember, this is also metro areas, so New York City, for example, is not limited to pricey Manhattan.)

Craig Alexander with TD Bank doesn’t see an American-style meltdown here either. He says the US housing collapse largely happened because of problems within the American banking system.

“At the peak of the US housing bubble about 40 percent of all mortgages being originated were sub-prime loans, in other words, high-risk, high-leveraged loans. Well, in the Canadian context, the mortgages are all income tested, the sub-prime market is probably about 3 percent of the total market. We aren’t seeing a lot of high-risk lending going on.”

I suggested to Alexander that this was shaping up into a far less sexy story than I envisioned.

“Sorry, in Canada it’s boring,” said Alexander.

But David Madani with Capital Economics wasn’t so sure that Canada and Toronto’s housing market is a boring story.

“We use the word bubble. We’re not afraid to use that word.”

Madani sees a lot of common factors between what happened in the US in the 2000’s and Canada today.

“We see the run-up in household debt, which is now almost as high as it was in the United States. We see the same run-up in the homeownership rate, just like what we saw in the United States. And then finally, of course, we’re also seeing the over-building and the new home construction, and this is particularly true in the condo market in cities like Toronto.”

Toronto is putting up the most high-rise buildings – that’s anything from 12 to 39 floors – of any city in North America: 132. By way of comparison, the top US city is New York. It’s building 86 high-rise towers.

Amy and Chris Poole, the young couple looking to buy a place, are well aware of all of the construction in Toronto.

“Standing from our balcony there, we can see 14 cranes,” said Chris.

Chris has heard the warnings that Toronto is building too much too fast. But he said he knows the other side of the argument, “where I’m like maybe we are behind what London, New York, what San Francisco is all about. Maybe this is sustainable, maybe this is the way things are going to be for a while. It’s hard to tell.”

Most economists and real estate insiders do agree that real estate values in Toronto will almost certainly be higher in 20 years. So for a young couple looking to invest for the long-term, there’s really no bad time to buy. That is, if there’s something they can afford to buy.

A version of this story also appeared at BBC News.

BONUS

How to Build a Housing Bubble

By David Weinberg and 99 Percent Invisible

Wallace Neff, Courtesy of Jeffrey Head

By far the best design podcast around—and one of the best podcasts, period—is Roman Mars’ 99% Invisible. On it he covers design questions large and small, from his fascination with rebar to the history of slot machines to the great Los Angeles Red Car conspiracy. Here at the Eye, we will be cross-posting his new episodes so you can check them out, and we’ll also host excerpts from his podcast’s terrific blog, which offers complementary visuals for each episode.

His most recent show—about bubble houses—can be played below. Or keep reading to learn more.

If you were a movie star in the market for a mansion in 1930s Los Angeles, there was a good chance you might call on Wallace Neff.

Neff wasn’t just an architect–he was a starchitect. One of his most famous projects was the renovation of Pickfair, the estate owned by the iconic silent film actress Mary Pickford, and her husband Douglas Fairbanks. If you were lucky enough to be invited to dinner at Pickfair you might find yourself seated next to Babe Ruth, the King of Spain, or Albert Einstein. Life magazine called Pickfair “only slightly less important than the White House, and much more fun.” Neff designed estates for Charlie Chaplin, Judy Garland and Groucho Marx, and his Libby Ranch is now owned by Reese Witherspoon.

But it was the 1,000-square-foot concrete bubble house where Neff lived out his final days that he considered one of his greatest architectural achievements.

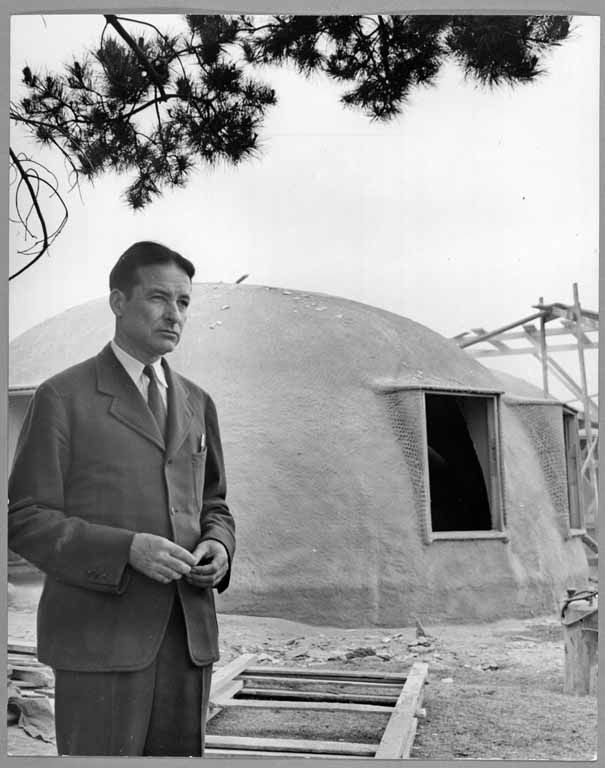

Wallace Neff at an Airform construction site.

Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Near the end of World War II, architects were anticipating the post-war housing shortage. Neff wanted to create a solution that would not only meet this demand, but address the need for housing worldwide.

The idea came to Neff one morning when he was shaving. He looked down and noticed a soap bubble that had formed on the sink. He reached out and touched it. The bubble held firm against his fingertip. That was the moment the idea struck him. He could build with air. He could make a bubble house.

Having already made his fortune as an architect for the rich and famous, Neff wasn’t in it for the money. He wanted to engineer an innovative way to provide low-cost housing.

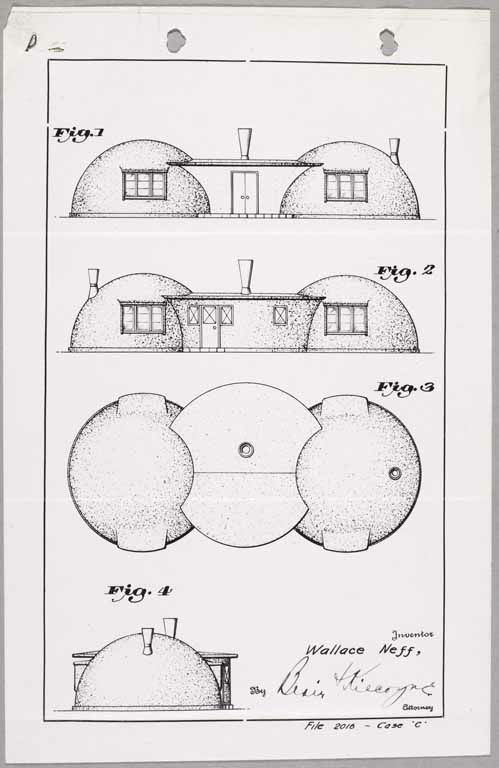

Dome-shaped living structures were not a new idea. The indigenous Acjachemon of Southern California had wickiups, the Ojibwe had wigwams, and the Inuit had (and still have) igloos. During Neff’s lifetime, Buckminster Fuller was creating his own circular solution to the housing shortage: The Geodesic Dome. (See 99% Invisible Episode #64). But Neff’s so-called Airform design was unique.

One of Neff’s patent drawings for a double-bubble house.Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

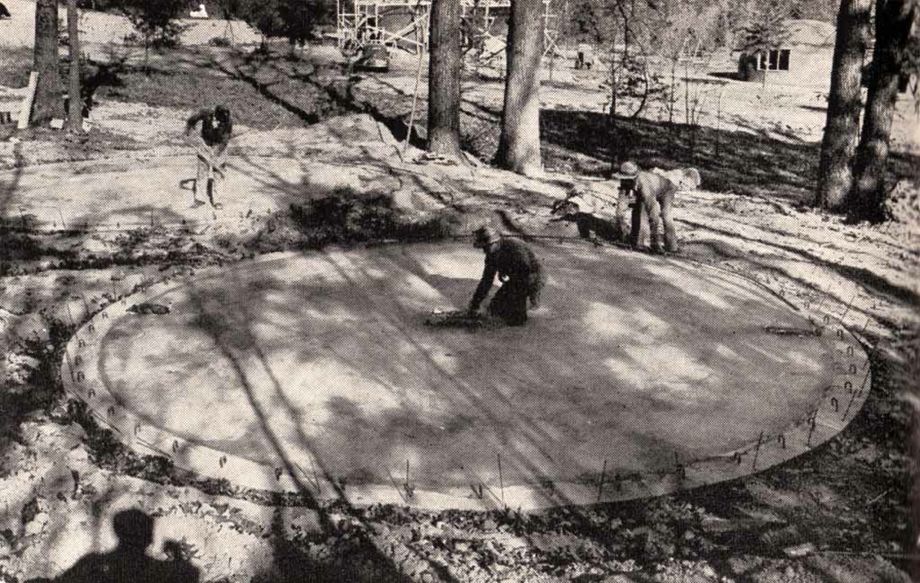

First, a big slab of concrete was poured in the shape of a giant coin.

Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Next, a giant balloon was inflated and tied down to the foundation using steel hooks.

Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

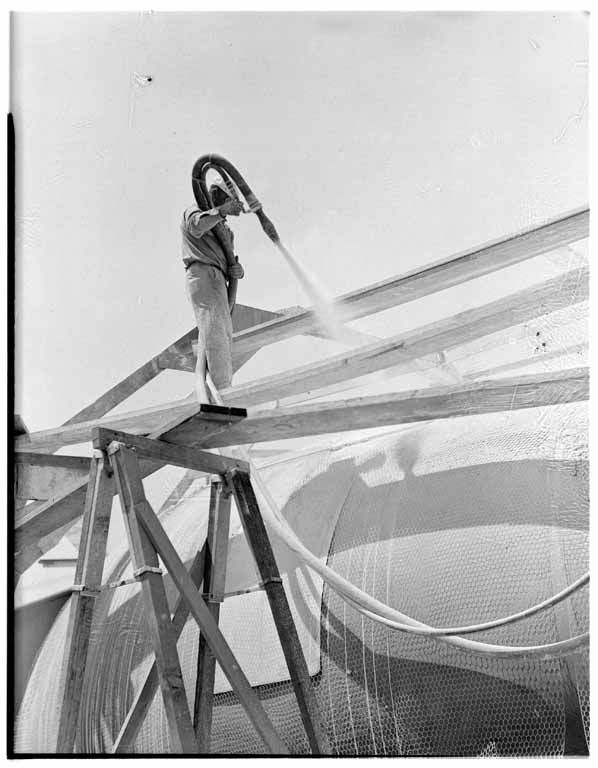

The inflated balloon was coated in a fine powder, then covered with gunite, the product of water and dry cement mix combined at high pressure and shot out of a gun.

Huntington Library, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Two men with a balloon and a gunite machine could turn a bare patch of soil into a bubble house in less than 48 hours. After the gunite dried the balloon was deflated and pulled out through the front door so it could be used again on the next house.

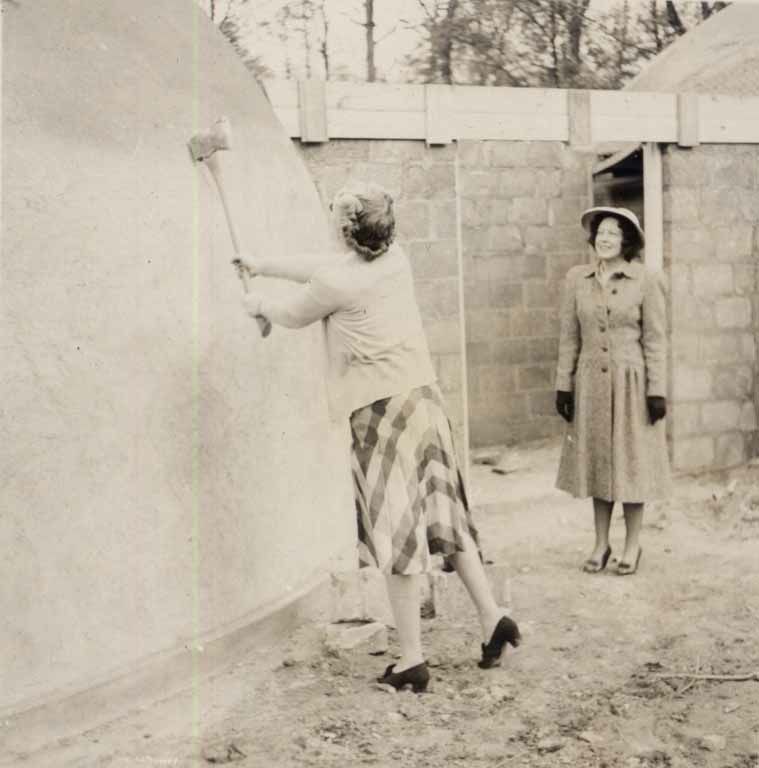

Dried gunite was more than twice as strong as regular concrete. Neff was so confident in his design that he would invite people to bash the walls of the bubble with the back side of an axe. The axe would just bounce off.

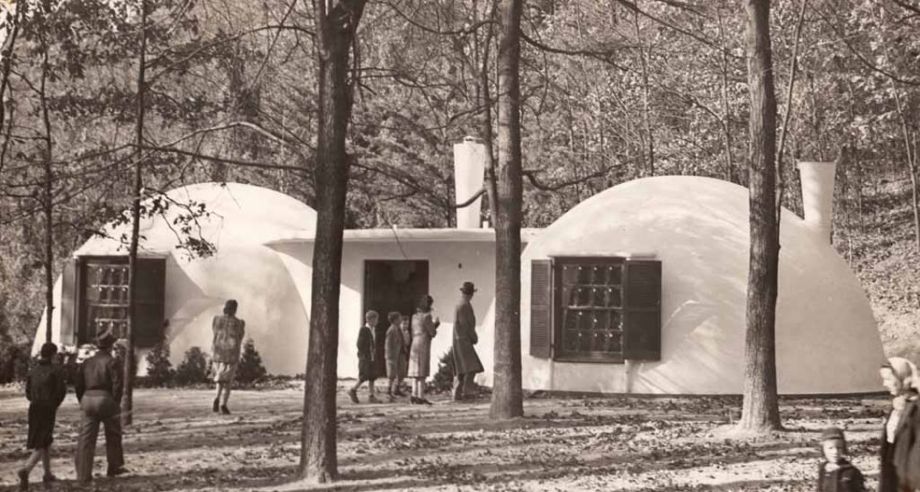

Courtesy of Steve Roden and Jeffrey Head

In October of 1941, Neff began construction on a community of 12 bubble houses in Falls Church, Virginia. Paid for by the federal government, it housed government workers. The neighborhood would eventually take on the nickname Igloo Village.

Life in a bubble house could be problematic. Round rooms were challenging to furnish, and the concave walls were not conducive to hanging pictures.

Huntington Library, Maynard Parker Collection

Igloo Village was isolated in the middle of the damp woods, and mold would creep inside the house. Kids from neighboring towns liked to drive by to ogle the bubble houses at night, disturbing the peace with their glaring headlights.

Nevertheless, Neff was able to land a few more clients. The Southwest Cotton Company hired him to build a desert colony of bubble houses in Litchfield Park, Arizona. Loyola University in Los Angeles ordered a bubble house dormitory. And in 1944, the Pacific Linen Supply Company commissioned a bubble structure 100 feet in diameter and 32 feet high–the largest ever built.

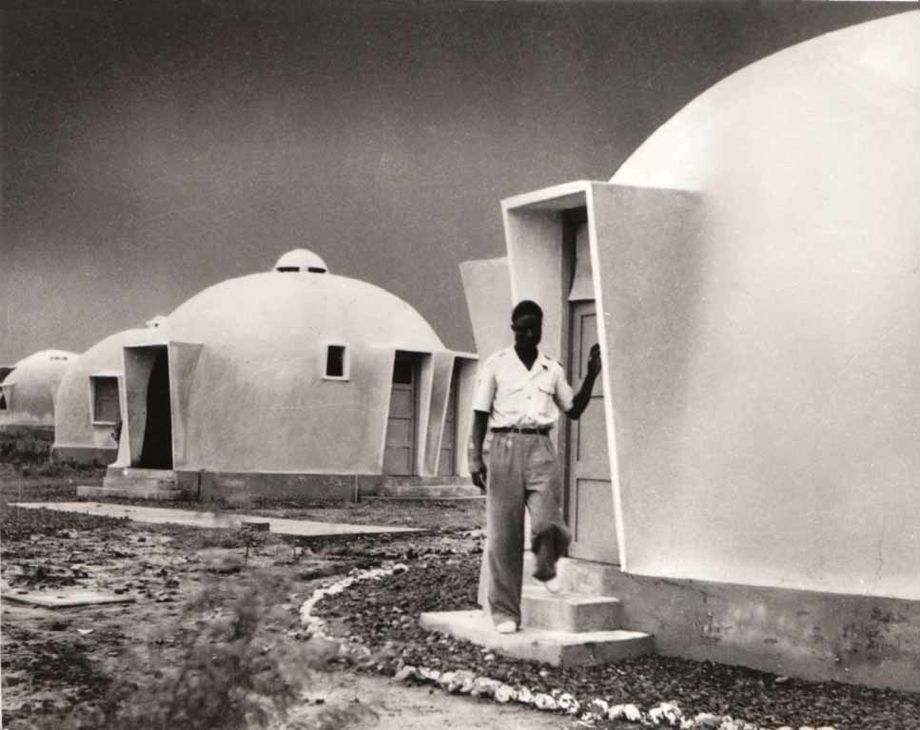

Neff’s bubble eventually burst, as all bubbles do. With the exception of a structure in Pasadena that Neff himself lived in, every one of Neff’s bubble houses in the United States have been demolished. But his idea spread to Pakistan, Egypt, Liberia, India, Jordan, Turkey, Kuwait, South Africa, The Virgin Islands, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Cuba, Brazil and Dakar, where many of the 1200 bubbles houses built in the 1950s–the biggest collection anywhere–are still around today.

Huntington Library, Courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Wallace Neff, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Candice Felt, courtesy of Jeffrey Head

Special thanks to historian Jeffrey Head, author of No Nails, No Lumber: The Bubble Houses of Wallace Neff.

To learn more about Neff’s bubble houses, read the rest of the 99% Invisible post or listen to the show. 99% Invisible is distributed by PRX.